If you are new, welcome, and for subscribers, welcome back. I am J. J. Bartel, Author, Botanist, Historian, and Gamer. Take note of the Author and Botanist. While I enjoy writing casual fiction and nonfiction, I also would like to write academic nonfiction, the kind of material one finds in journal articles. The thrill of experimental design, growing plants, learning new things, and sharing that info with others is quite lovely.

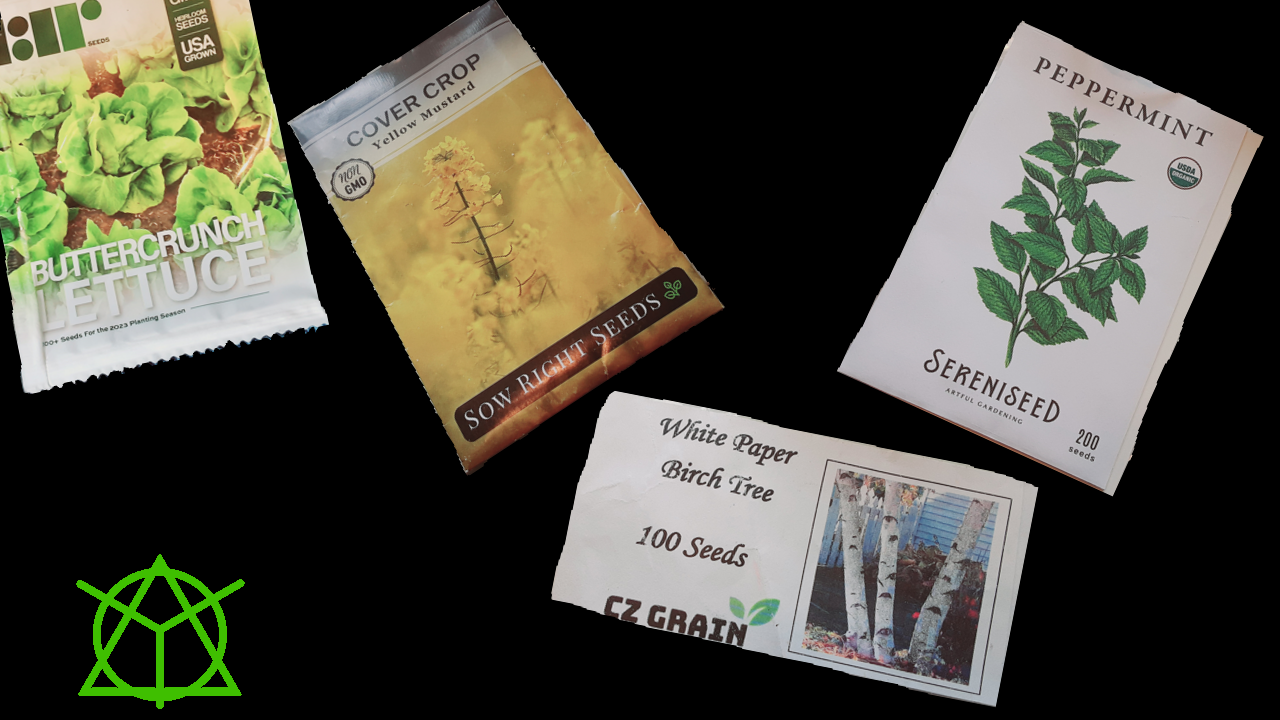

Eventually, I settled on doing a companion planting experiment. I am interested in trees, and the American Paper Birch is botanically and historically significant. Beans, specifically legumes, are known to release nitrogen compounds into the soil. That extra nitrogen is useful to most other plants, bacteria, and fungi. Mustards are known for various sulfur compounds that often kill fungi. This chemical is often exudated or released into the soil. Mints are known for terpene alcohols, such as menthols, that kill bacteria. It’s found in the leaves and will exudate these chemicals into the ground. Lettuces are known to be nonreactive and grow well around other plants because they are a primary carbon container for water. I mean that. Lettuce is mostly carbon and water, even more than most plants. Its entire survival mechanism is based on being so biochemically plain that it has much lower nutrient requirements than other plants. There is a reason why an allergy to lettuce is nonexistent. There’s nothing to react to! Back on topic. Many trees rely on helpful bacteria, fungi, or other plants to fight off bacterial, fungal, or viral infections or get extra nutrients. Will these companions help or hinder American paper birch tree germination?

If I could do an experiment, it would have to fit in my apartment yet contain enough reps or repetitions of the control and variables. So in an experiment, the control is what you don’t change, and the variables are the parts you change. You compare the control to the variables to get results. This experiment was planned to have 4 controls, 5 variables, 7 reps each, for 63 total units. I chose plastic bottles from the same manufacturer to make things work. It’s also important to note that the more data one has, the more valuable an experiment is. Repeated, high-data experiments make for an excellent material for academic publishing. While many professors focus on high-impact journals with high readership, grants it is not the only way. Many journals of mid-impact, narrower focus, have lower barriers to entry, and still contribute valuable info for the academic community. These journals are far more likely to take the data from this experiment and publish it. That’s assuming the experiment works.

Because I was still figuring out my phone functions, I just took many pictures, hence the slideshow rather than the video. I started growing some spare seeds in spare containers to dry-run watering ratios. Dry runs are when you test aspects or entire experiments without using valuable materials. This helps experimenters find and address issues early before the actual experiment. Over time, I got more and more water bottles, took off the plastic label, and took the top off to the first ridge. They were filled with standard miracle-grow potting soil to the third ridge from the top. According to some back-of-the-hand math, liquids filled to the third ridge are around 13 fluid ounces or roughly 358 grams of soil in each container. I used the cut lids as measuring cups for the water and shoved the tops back on the bottles, trapping the moisture inside.

Only the Birch tree seeds needed prep. They are meant to be stuck in a fridge for a time. The chill is like winter, so the sun will warm them up when they get planted, triggering germination. All other seeds could be planted on the experiment’s first day, Mother’s Day, May 14th this year.

Starting with the bottom right bottle, I planted birch, bean, mint, mustard, lettuce, birch and bean, birch and mint, birch and mustard, and birch and lettuce. I snaked up the collum that went across left once, then down, and so on. Going up, then snaking through the bottles until I got to the bottom left. This allowed each control and variable to be spread out so that their position on the table would not change the growth. Each had access to similar amounts of sunlight, water, and other factors. The plan was to record heights weekly, germination, colydeton formation, first leaf formation, and first flower. When I harvested the plants, I would record the harvest day, leaf, and fruit weight.

In the world of experiments, it’s common knowledge that over 90% fail. This, sadly, was no exception. My fridge needed to be at least three degrees cooler for seed dormancy. It also explained why my parent’s fridge has less spoiling than mine. Everything else grew, germinated on time, and I at least got some salad greens out of the deal. I will try to revamp this experiment, perhaps getting seedlings or shoots, maybe getting wider containers, or setting the fridge to something colder if I go for the seeds again.

You might ask, why show this loss? Well, learning from failures is the cultivating fertilizer for greatness. Until next time let’s cultivate some greatness.

Your concluding comment is an insightful perception…with your writing, you’re able to entertain, inform, and educate. While accomplishing these, you faithfully take it a step further and offer the merits of a moral lesson—all this makes your writings so worthwhile of a reader’s time!